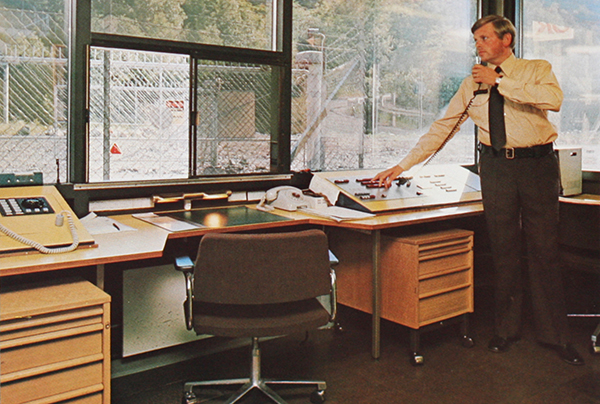

An alarm center in 1979

The result of an exhibition

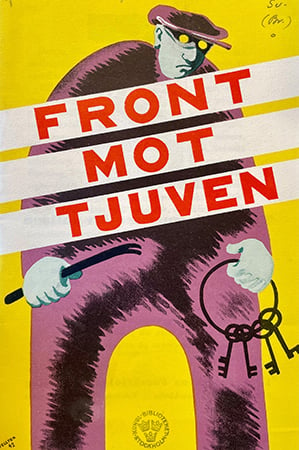

Posters depicting a burglar in a domino mask popped up in Swedish cities in 1942. The posters advertised the traveling exhibition “Front against the thief,” arranged as a response to a rising crime wave hitting Sweden. When the exhibition was held in Stockholm, it gathered the insurance industry, telecom company LM Ericsson’s alarm systems division and the police. Erik Philip-Sörensen, already recognized as Sweden’s leading expert on security, was invited.

The poster from the exhibition Front Against the Thief. Photograph: private

The discussions held at the exhibition marked a turning point in the history of the Swedish security industry. There was a consensus that Sweden needed a new, modern security company to keep up with increased crime using traditional guarding methods. Erik was already the CEO of Förenade Svenska Vakt, but since time was of the essence, a new company – Städernas Vakt – was founded, with Erik at the helm of operations. He was now the CEO of two major security companies!

Peacetime use for wartime innovations

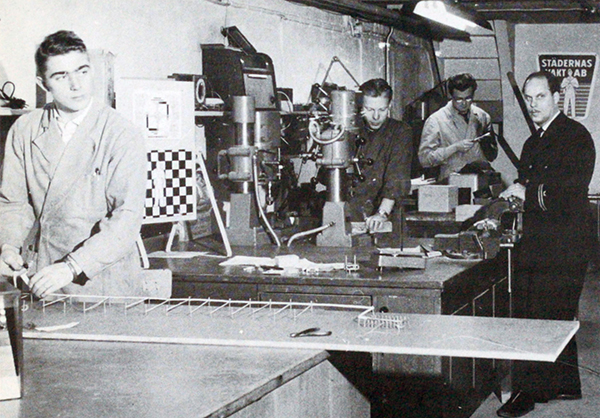

World War II had accelerated the pace of innovation in the security field. Following the war, a lot of technologies were repurposed for peacetime security applications. Radars, sensors, and televisions had the potential to take the security industry to the next level. Städernas Vakt established a technology division already in 1948 with the objective of refining and adapting these technologies for peacetime security purposes.

Städernas Vakt's technical department in 1956. From left to right: Lars Palmgren, Nils Nilsson, Nils Lindström and Gunnar Brodén

Collaborating closely with telecom giant LM Ericsson (later, just Ericsson), Städernas Vakt utilized existing central alarm stations to offer security solutions. After winning a significant contract from the Swedish Postal Service, security services needed to be expanded nationwide. The new contract also emphasized the need for new technology, as relying on traditional security to serve a nationwide client would excessively squeeze profit margins.

In Sten Söderberg’s book about Securitas, Helga Zimmerman, Städernas Vakt’s first hire, recalls the early days when she needed to wear many hats in her role: “I was a cashier, bookkeeper, central alarm operator and the ‘no-nonsense woman at the service counter’”. The first office in central Stockholm did not have any desks, so Helga had to keep the accounting books in her lap. Fortunately, ten years into operations, Städernas Vakt had over 600 clients across 37 branches. And the office had desks!

Helga Zimmerman extends congratulations to the United Danish Guard Company in 1951

The birth of Securitas Alarm

A year after Städernas Vakt founded its technology division, the other major security company, Förenade Svenska Vakt, followed suit and established Securitas Alarm (the first time the name Securitas was used in Sweden).

Being the CEO of two competing companies was not ideal. The board thought this was a dubious double role, so Erik stepped down as CEO of Städernas Vakt. To avoid Städernas Vakt and Securitas Alarm undermining each other's client base and prospects, Erik decided to let the Stockholm-Gothenburg railway be the line of demarcation. Securitas Alarm's operations were to the south of the tracks, while Städernas Vakt's were to the north.

Already from its founding, Securitas Alarm ventured into the world of automated security systems. The new division was tasked with developing and implementing technology solutions, primarily focusing on burglar alarms and other systems complementing traditional guarding services. The aim was to stay ahead of the curve in an industry that was increasingly moving toward automation for enhanced efficiency and reliability. Initially, Securitas Alarm was more of a financial burden than a revenue generator but nevertheless remained competitive.

Joining forces

To effectively serve the Swedish Postal Service, a collaboration was established between the two companies. This cooperation eventually led to Securitas acquiring Städernas Vakt. The new company was based in Stockholm and became the dominant force in technological security, with its combined market shares.

An edited photograph of two officers from the Northern and Southern tip of Sweden, illustrating nation-wide coverage

Increased use of technology in guarding became a reality due to two separate developments: the crime wave in the 1940s that brought different parts of society together in a collaborative effort, and the new technological advancements propelled by World War II, making wartime inventions available for peacetime use. Combined, those factors reshaped the industry and put Securitas on a new trajectory, a path that the company is on to this day.

![]()

Securi-Coll

With 110 employees (of which many were engineers), an office in Stockholm, and a factory in Tewkesbury, England, Securitas Alarm started to develop burglar alarms, detectors, and computerized systems for access control. The first breakthrough came with Securi-Coll, a fully automatic access control system. First presented at an International Security Ligue meeting in Turin, Italy, in 1961, it was an immediate success.

Today, we’re all accustomed to automatic access control, but in the early 1960s, it was something completely new. With Securi-Coll, employees carried an identity card and inserted it into a card reader at the gate. After entering a four-digit PIN on a keypad, the employee’s ID number – along with the date, time, and place of entry – was registered on a punch card. A time-consuming and labor-intensive procedure was completely automated, marking a major leap forward for the industry. This was also the first time in history that four-digit PIN codes were ever used.

Securi-Coll in action

From gas stations to banks

Strengthened by the success of Securi-Coll, Securitas Alarm’s engineers scanned the market for new uses of security technology. Around the same time the automatic access control solution debuted, the banking sector was undergoing a significant change. The shift from cash to checks for salary payments resulted in higher handling costs due to increased volume in check processing. And when Swedish banks were no longer allowed to stay open on Saturdays, the situation became too hard to handle. Something had to be done to keep up with the demand for banking services.

In the meantime, Securitas had developed additional uses for Securi-Coll. In 1965, a mechanism for automated services such as time registration and self-service purchases was developed. Shortly after obtaining its patent, Securitas introduced the world's first automated payment systems for gas stations in Sweden, enabling transactions with cards and codes without the need for service personnel. Could this technology be the solution to the bank’s capacity problems? An automated solution for cash withdrawals would help get the pressed banks back on their feet.

The ATM race

The Swedish Savings Bank encouraged Securitas Alarm to modify its payment system for gas stations to be used also for cash withdrawals. In 1967, an agreement between Securitas, the Swedish Savings Bank’s data centers, and IBM was established with the aim of creating an online-connected automated teller machine (ATM). However, due to a delay, the initial ATMs only worked offline, meaning the ATM was not connected to the clients’ bank accounts.

The delay led other competitors to develop similar products and beat Securitas to market. On June 27, 1967, the first automated teller machine – the De La Rue Automatic Cash System – opened in Enfield, London. Only nine days later, on July 6, Securitas’ ATM opened in Uppsala, north of Stockholm. It's worth noting that the ATMs in both Enfield and Uppsala were not linked to account balances, allowing withdrawals only once per day.

Less than a year later, on May 7, 1968, Securitas and the Swedish Savings Bank made history by launching the world's first online-connected ATM at Oxie Sparbank in Malmö. This innovative machine was directly linked to the bank's computing systems, a significant advancement in banking technology.

Since the 1960s, ATMs have moved from punch cards to magnetic stripe cards to chip cards to today’s contactless payments using smartphones and watches. The legacy of Securi-Coll continues to influence modern financial interactions. Users are still prompted to authenticate transactions, often by entering a four-digit PIN code. Modern systems, as with the Securi-Coll concept, meticulously record every detail of our transactions: what we purchase, when, and where, just like it works today.

Securi-Coll access control cards, the National Museum of Science and Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, photo: Peter Häll

Introducing industrial television

Television technology became widely accessible after World War II, and television ownership became commonplace in households across Western Europe and America. With the surge and development of television screens, a potential for revolutionizing surveillance using cameras and television screens to monitor sites and valuables arose. Securitas Alarm seized this opportunity by introducing what was called industrial television (ITV) in the mid-50s.

Early systems were far from today’s plug-and-play technology; serious engineering skills were needed to manage the complexities of the cameras and cables. The idea with ITV was to make monitoring more efficient without increasing the staff, ultimately resulting in reduced costs. The head of Securitas Alarm’s ITV department, Eric Ingman, took on the challenge to make camera surveillance easy to use.

With Eric’s engineering skills, Securitas ITV eventually became so stable that it required no complicated procedures, making it possible for Securitas’ service technicians to manage the system. The system allowed for remote control, with image transmission possible even for long distances. All cameras could be managed via a low voltage and the control panels became user-friendly. Cameras could be locked in place at location, making them accessible only to service technicians.

When the big Rembrandt exhibition travelled to the National Museum of Fine Arts in Stockholm, Securitas Alarm was entrusted to install ITV, replacing the ultrasonic alarm method that had been used to protect similar exhibitions in the past. By 1961, Securitas Alarm had become the leading supplier of ITV systems in Sweden, accounting for 90% of all systems in use.

Embracing technology while preserving human expertise

During the 1960s, an increasing number of industries began to acquire ITV installations and Securi-Coll as surveillance tools, leading to Securitas becoming a Swedish export success. The primary reason was the cost reduction achieved by allowing the same security personnel to monitor several gates and entrances simultaneously.

It might seem odd that a security company would engage in selling equipment that could reduce its own workforce and, consequently, its revenue. At this time, Securitas had become a technology-driven security company with the purpose of making surveillance work as efficient and cost-effective as possible for clients. The aim was to offer the highest quality security systems possible, a mindset that still exists today.

In June 1968, Industria magazine featured an interview with Erik Philip-Sörensen, the group CEO, with the headline “Security is ultra-modern technology – but people are still the most important.” In the interview, Erik reflects on his remarkable story, from starting out with just 300 kronor to a turnover of 150 million kronor 34 years later. When asked about the secret to his success, he highlights two things: economic carefulness and the ability to attract great people.

The topic of the interview is modern technology, but Erik chose to highlight the officer’s role in automated security systems. He mentions that the role of the officer will require a high and diverse level of competence since the officer must be proficient with the electronic aids available and adept at processing the incoming information. Security officers need to respond swiftly and appropriately to any situation, he continues. This includes having a solid understanding of, for example, boilers and machinery and being skilled in firefighting techniques, even though in most scenarios, the wisest course of action is to alert the fire brigade.

Strategy lasting over time

Fears and anxieties about automation were as widespread in 1960 as they are today when artificial intelligence (AI) is fueling concerns about job displacement and other societal impacts. In fact, the question of whether technology will replace humans has been a recurring theme since the Industrial Revolution. And in the security industry, the issue has always been a particularly hot topic.

The significance of human ingenuity was a clear conviction for Erik already during the rise of electronic technology, and it remains a core principle for Securitas in today's digital revolution. For Securitas, the answer is the same as it was then: as businesses navigate a tech-driven world, it is crucial to recognize that both technology and people are indispensable. Together, they form a powerful alliance to ensure our security.

In the present day, with Securitas’ 341,000 professionals worldwide, the industry still embraces this dual role: having an on-site presence using technology, driven by data. This presence is the backbone of modern security operations – and a testament that humans are not replaced but rather empowered by technology to enhance our capabilities.

![]()

The shift from tradition to technology

The Meeting of Waters is a top tourist attraction in Manaus, Brazil. This is where the dark Rio Negro and the pale sandy-colored Amazon River float alongside each other without mixing, creating a striking natural phenomenon. This confluence also happens to be a perfect analogy for Securitas’ initial ambition to integrate technology and guarding at the end of the 1980s, resulting in two divisions running in parallel without being fully integrated. The comparison with the two rivers is borrowed from Carl-Henric Svanberg, who was in the middle of the action.

Following a period of uncertainty and lack of expansion opportunities, Melker Schörling (1947-2023) became the CEO and President (and concurrently an owner) of Securitas in 1987. Melker had a sincere interest in the development of individuals as well as businesses. He was always open to ideas and allowed space for contemplation before making decisions. It was Melker who laid the foundation for modern-day Securitas by focusing on clients and advocating for a decentralized business model.

When Melker joined, Securitas was primarily known for traditional guarding, with technology playing a relatively minor role, constituting about ten percent of the offering. In an effort to better make use of modern technology, the promising newcomer Carl-Henric Svanberg was promoted to President of technology operations. His first task was to realize Melker’s vision of a modern, technology-driven security company.

The tension between tradition and innovation

In the late 1980s, Microsoft Windows 1.0 was released, the first pocket-size cellular phone was launched, and the number of computers worldwide reached 100 million units. Virtually all industries, security being no different, were grappling with how to capitalize on the fast technological advancement. The shift from an analog to a digital world had begun.

To keep up with developments, Securitas entered a phase of innovative ideas that was presented at a fast pace. But since guarding operations are deeply rooted in history, the introduction of new technology brought conflict to the surface. But Melker and Carl-Henric were decisive; they knew that rapid change was needed to improve efficiency and stay ahead in the business.

Introduction of the Market Matrix

Since more advanced alarm systems required a tailored approach, a more exact segmentation was needed. This was when the Market Matrix was born. With this tool, all clients were divided into segments based on their line of business (small and medium-sized, large banks) and the size of their location (factory, office, home). For instance, a chain of petrol stations, though considered large, is made up of sites with distinct security needs. Likewise, the security requirements vary a lot between a bank's headquarters, a power plant, and a residential home.

The Market Matrix helped Securitas tailor security solutions accordingly, whether it involves centralized monitoring for a chain of stores or onsite security for a large facility. When applying the model, it became apparent that the industrial sector, for example, expressed an initial reluctance to the use of technology in their security solutions.

The banking sector, on the other hand, and in particular the Central Bank of Sweden and leading Swedish commercial banks, were among the first to embrace new technology in combination with traditional security. Their interest resulted in the creation of a separate technology department within an alarm center solely for the banking sector. The new alarm center for banks became an immediate success, and companies from all over the world visited for inspiration. The tide was turning.

An officer in charge of access control at the co-operative union, Stockholm, Sweden

Securitas Direct

The shift towards greater technology integration raised important questions about Securitas' role in providing technology compared to the cost-effectiveness of using external solutions. These strategic considerations highlighted the need for skilled people who could handle and fix system issues. As a result, it became evident that having a dedicated technology department for installation, maintenance, and support was essential.

As a result, Securitas Direct was created in 1988 as a home and small business alarm company. Securitas Direct was treated as a genuine startup – developed within the company but run separately. Dick Seger was appointed the in-house "intrapreneur" for the project and initially did everything himself: from packing boxes in the morning to making sales calls in the afternoon.

Melker’s and Carl-Henric’s vision paid off; the business grew at an incredible rate. From 67 installations at the end of 1988 to 3,850 in 1990. However, one vital factor was missing: a go-to-market model that leveraged what Securitas Direct was offering homeowners. Installation of wired alarms was cumbersome and time-consuming – to install a home alarm system, it could take one to four days, depending on the age of the home’s wiring.

When wireless technology became readily available, it proved to be the missing piece in the go-to-market model. Wireless technology installations could now be done in a matter of hours. With installation costs and labor time reduced significantly, the company could now serve more homeowners, leading to the success of Securitas Direct.

Thirty years after Dick Seger’s one-man show, Securitas Direct had two million clients in 14 countries. According to former CFO Håkan Winberg, the key to success was that Securitas Direct was allowed to begin as a start-up and that Dick reported directly to group management, underscoring the difference between security for homes compared to large clients and banks.

The birth of Securitas Technology

In 2006, Securitas Systems (comprising alarm, monitoring, and access control systems) and Securitas Direct were spun off to shareholders and listed on the Stockholm Stock Exchange. Former CEO Thomas Berglund cited the rationale behind this distribution as allowing the companies to achieve their full entrepreneurial potential. Securitas Systems was rebranded as Niscayah and continued to be an important client of Securitas. In 2006, Securitas Direct was delisted from the Stockholm Stock Exchange, sold and rebranded as Verisure in 2009.

The demand for security technology prompted Securitas to attempt to repurchase Niscayah in 2011. However, Securitas lost the bidding war to STANLEY Black & Decker. Eleven years later, in 2022, Securitas successfully managed to acquire the company, which was then operating as STANLEY Security. This acquisition led to the creation of a new division called Securitas Technology, encompassing STANLEY Security and Securitas Electronic Security. Additionally, STANLEY Healthcare was rebranded as Securitas Healthcare.

Technology is here to stay

Securitas' transition toward the integration of more technology has been a subject of debate since the 1950s, particularly the balance between traditional security services and technology. The creation of Securitas Technology has, once and for all, created an exceptional provider of tech-enabled security solutions and a leading partner to clients on a global scale. With a combined client proposition and a strong sales structure, Securitas can deliver higher, more profitable growth than ever before.

Except where indicated, all photographs are taken from the book Vakt av värde by Sten Söderberg (1979). Photographer unknown. If you own the rights, please contact press@securitas.com.